Have the Humanities Abandoned Beauty?

We spend so much of our time as students reading and analyzing literature. We seek to unlock the inner mechanism of its meaning like mathematicians working out a proof. Have we forgotten, amid all these heady efforts, how a book or a poem at its best can make us feel?

From the fifth grade on, my first concern in the classroom was always literature. Books, poems, plays: I dug through them hungrily. It was love that pushed me into the world of stories. A love for the feeling that I would come to know as transcendence: an utter, deeply pleasurable awe at an encounter with beauty. Those moments when the chaos of the lived world weaves itself wondrously together into a braid of sense — what American poet Robert Frost called “a momentary stay against confusion.”

So, I was startled to realize that the question of beauty had been altogether absent from my English classrooms. That is until the spring of my senior year of college.

My professor distributed a packet of poems stripped of their authors’ names. He then asked us a simple question: which of these poems is good and which of them is bad?

My class, made up of literature students, lovers like me of words, didn’t know what to make of this question. They could tell you the meter of the poem, could precisely explicate its cadence and rhyme scheme, could even speak with great eloquence towards the poem’s point. But how does one decide whether a poem is any good? And if it is, as I suspect, a question of beauty, well…what is beauty? What makes a poem, a book, a character beautiful? And, why aren’t we talking about these things in class?

What’s to be done about literature?

The answer to that last question starts somewhere around the turn of the 19th century. Until this point, students and teachers of literature were concerned mostly with evaluating the relative worth of a piece of fiction; that is to say, whether a particular poem, novel, or drama was well-written and why. This practice of literary criticism certainly persists, but has been knocked off its high plane of authority by literary theory.

With the writings of mid-19th Century philosophers like Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche,Karl Marx, and later, Sigmund Freud, a general suspicion crept into the realm of literary criticism. Responding to the effects of the Enlightenment and a cultural milieu increasingly bereft of the institutions of religion, stable family units, and tight-knit rural communities, these thinkers were skeptical of the possibility of universal truth. Of Authority of any kind, in fact. They posited that the modern human subject is somehow detached, or alienated, from the objects it perceives, from a sense of free will, from the work he produces, and even — in Freud’s case — from the inner machinery of his own mind.

Pair this brewing skepticism with the incomprehensible violence and destruction that shaped the first half of the Twentieth Century. With this you arrive at a shell-shocked world of readers no longer interested in the question of beauty in art. As cultural theorist Teodor Adorno said, “There can be no poetry after Auschwitz.”

Enter the literary theorists

They spend their time inspecting literature — what they refer to as “text” — through multiple lenses of skepticism. They’re searching for the underlying and unspoken forces that produce a work. In a way, they have modeled themselves and their methods after the scientific method of hypothesis and experiment. They dissect the work they read and write about.

There are endless theories of literature ranging from feminist critique to psychoanalytic theory to critical race theory. All of them are fascinating and useful in their own right. But none of them is particularly concerned with the feelings of pleasure or delight or profound sadness that a piece of literature might inspire in its reader.

Back to my professor’s question: What makes a good poem?

My answer: A good poem is one that makes you feel more completely alive.

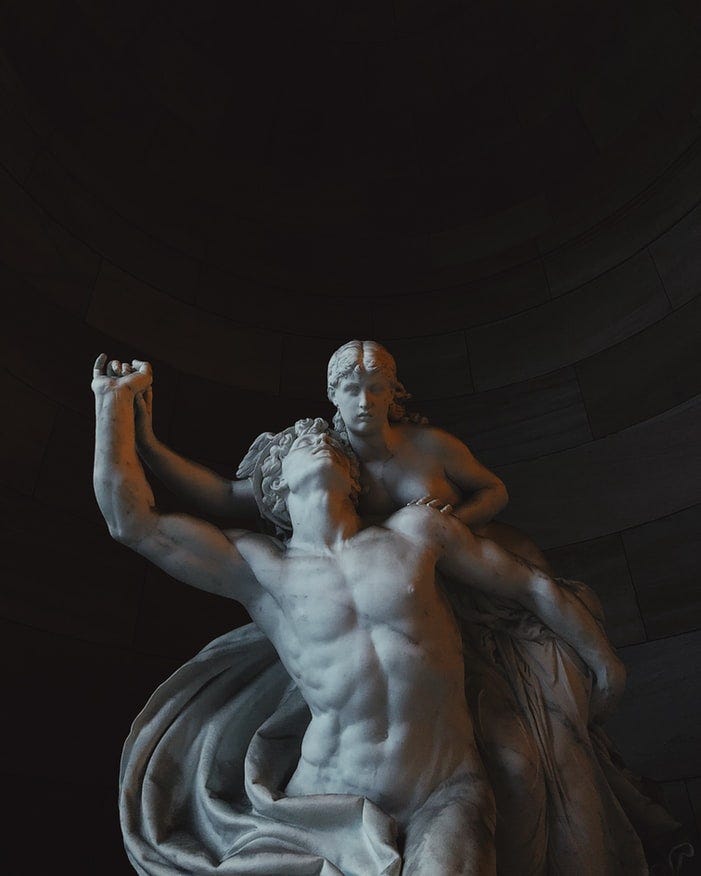

Perhaps a good poem makes you feel hopeful or optimistic or deeply sad or less afraid of death or — in the most venerable cases — unable to think much at all, flooded with too much feeling even to categorize it. This is what the Romantic poets referred to as an experience of the sublime.

Beauty is difficult to talk about and even harder to write on. But if we can give voice to the way that literature makes us feel, we might begin to uncover why it makes us feel that way and how. This process of discovery turns the searchlight of literature inward, and guides us nearer to the gift of self-knowledge. With invisible cords of deep feeling, great literature connects us to readers and writers across vast space and vaster time. It braids our souls into a borderless and unknowable web of readers dead and living, experiencing beauty, together.